Featured Book

Against the Grain

A Deep History of the Earliest States

It used to be thought that agriculture made living in settled communities possible, but recent archeological research indicates that ancient peoples began cultivating grains in fixed locations long before societies with central governments were established.

The widely-accepted story of our past is that we humans started as nomadic hunter-gatherers with limited skills, becoming productive and civilised only when we were organised into fixed settlements for the purpose of growing grains—settlements with infrastructure, divisions of labor, hierarchies of authority, tax systems, and other marks of statehood. James C. Scott goes against the grain both in questioning that story and in offering a contrarian perspective on the role that grains have played in our ancient past. From his perspective as a political scientist, he asserts that when early humans lived in settled communities and devoted their time to growing grains and caring for animals, they did not fare better than their nomadic contemporaries and were often worse off in that their diets were more limited, their health less robust, their lives more arduous, and their existence more precarious.

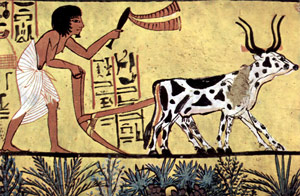

In presenting this perspective, Scott takes the reader deep into the distant past, from 12,000 BCE onward, citing multidisciplinary evidence while offering his own interpretations based on considerations of human behavior and motivations. He looks at various regions of the world, including Egypt and China’s Yellow River Valley but focuses heavily on southern Mesopotamia, with particular consideration for what is known about life in that region from 3000 BCE onward.

It used to be thought that agriculture made “sedentism” — that is living in settled communities — possible, but recent archeological research shows that there’s a gap of about four thousand years between sedentism and the adoption of agriculture. Ancient peoples began cultivating grains in fixed locations long before societies with central governments were established, he notes. “The first states in the Mesopotamian alluvium pop up no earlier than about 6,000 years ago, several millennia after the first evidence of agriculture and sedentism in the region.” Scott points out that state oversight and control were clearly not needed for people to become productive farmers.

Instead, skilled agriculture and animal husbandry existed side-by-side with skilled hunting and gathering. Recent archaeological discoveries in Jordan provide further support for this view with evidence that over 14,000 years ago, long before agricultural societies were established, nomadic peoples were grinding grain and baking bread.

Another common assumption is that states were formed to facilitate agriculture in arid regions where farming posed significant challenges. However, as Scott notes, southern Mesopotamia was not always the arid desert that it is now. In the Neolithic period, Mesopotamia, the land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, was a delta wetland that supported a great variety of sea and bird life along with a fertile area for growing food. Obtaining food in the region was easy at that time, so people had a strong incentive to gravitate to the area to take advantage of the many resources.

Rather than states arising to organize poor nomadic people into settlements of prosperous farmers, Scott suggests that the more powerful few imposed control on already thriving societies that had mastered the growing of grains as one source of food. The motivation of the rulers was thus not to help the people but to exploit them.

Grain-based societies were good targets because grain harvests are predictable and because grains can easily be monitored and taxed by those exerting authority. The goal, Scott notes, was to gain control over large numbers of people and turn them into a dependable workforce that would regularly produce a surplus of food. The rulers could then relieve themselves of the need to produce food and could concentrate on other endeavors. Enforced labor, including slavery, was thus essential to the functioning of a grain-based state. Because of this, rulers had difficulty hanging on to a workforce and for quite a long time generally had control of only very small areas, since people could simply move on and forge lives elsewhere.

“…in a total global population estimated at roughly twenty-five million in the year 2000 BCE, [states] were tiny nodes of power surrounded by a vast landscape inhabited by non-state peoples—aka ‘barbarians’,” Scott points out, and that Sumer, Akkad, Egypt, Mycebae, Olmec/Maya, Harrapan, Qin China notwithstanding, most of the world’s population continued to live outside the immediate grasp of states and their taxes for a very long time. States began to be major forces in people’s lives only from about 1600 CE.

Scholars have tended to see grain-growing societies as the true foundation of civilization, as if hunter-gatherers were intellectually inferior, without the dispositions and planning abilities needed to grow crops. Scott suggests, instead, that our early ancestors were astutely observant of the natural world and were well able to manage a great variety of food sources by engaging in foraging and hunting while also tending livestock and growing crops as needed with a variety of labor-saving techniques. He notes that such versatility and adaptability would have been much more likely to ensure the survival of a family or a society than a reliance solely on agriculture.

As states developed and concentrated their attention on domesticating a limited number of plants and animals, people became dependent on them. The more people focused on growing grains such as wheat and barley, the more their lives became circumscribed by the grains and the more they lost the breadth of skills of the earlier humans who grew crops to supplement what they caught and gathered in the wild. Scott suggests that it’s worth pondering that we may have lost as much as we gained by concentrating our efforts on growing the staples on which we depend so heavily today.

Although we think of life in settled communities as having significant advantages over nomadic life, settlers’ health was often compromised. When people lived continuously in close quarters with each other and their animals, pathogens could spread quickly, while the more limited diet of settlers reduced their overall health and made them more susceptible to life-threatening illnesses.

The prevailing assumption is that barbarians were unruly, brutish, inferior people who terrorized settled communities with raids and destruction—situations that required the intervention of rulers to protect settlers. However, the evidence shows considerable movement between people living in states and people living outside of state control. Both sides benefitted from trading with each other and from providing alternatives to each other’s lives. Throughout history, some non-state peoples have been attracted to the settled life and have been assimilated into states, while some settlers have been attracted to the nomadic life and have left the confines of the state for what they perceived as a better life.

From Scott’s unique perspective as a political scientist and an agrarian studies professor, he paints a positive view of non-state peoples, pointing out the many advantages of not being under the thumb of a ruling class. Ultimately, he shows that people under state control and those who were free of it were two sides of the same human coin: people who adapted to their circumstances in order to survive and prosper.

About the Book’s Author: James C. Scott, Ph.D., is Sterling Professor of Political Science, Acting Director, Agrarian Studies, and Professor, School of Forestry & Environmental Studies and Anthropology and Institute for Social and Policy Studies at Yale.

External Stories and Videos

Archaeologists find earliest evidence of bread

Nicola Davis, The Guardian

Tiny specks of bread found in fireplaces used by hunter-gatherers 14,000 years ago, predating agriculture by thousands of years