Featured Book

New World New Mind

Moving Toward Conscious Evolution

Robert E. Ornstein and Paul R. Ehrlich

Paperback edition 2000

The world that made us was one that changed little or not at all during a lifetime: tasks and social roles were passed down unaltered for millennia. Our biological evolution favored ancestors with limited perceptions and quick reflexes to deal with sudden threats. The world we made requires the opposite; the threats are invisible and long-term, like pollution and overpopulation, not a sudden wild hippo running amok. More people have been added in the 21st century than existed at the time of Christ, and the threats are different, Cigarette smoking, for instance, killed more people in the week of 9/11 – and in every week after it – than died in that tragedy. But we don’t notice. Our consciousness needs a new evolution to adapt to this world of slow, constant change and threat. New World New Mind presents a way forward.

Our climate is deteriorating, there are too many people for the Earth to support, and there are a great many severe social and political problems that seem unsolvable. The world is full of brand new and increasing dangers that most people ignore. And when enough people do notice a problem and decide to take action, the results are themselves often disastrous.

In New World, New Mind (“NWNM”), Robert Ornstein and Paul Ehrlich explain that we are causing our own problems because we have created a world where our basic mental functions are no longer suitable. We evolved over a period of millions of years to survive in small tribal families on the wild grassy plains of East Africa. Now the way we live has nothing to do with that time and place, but the mental tools that were developed to survive on the savanna have remained unchanged. These instincts were wonderfully adapted to the environment that shaped them. But that world, the world that made us, is gone. Now these same instincts are causing us to destroy the world that we made.

The threats we face are of our own making, and we can unmake them. If people learn how we have come to this point, we can restore our hope for the future. NWNM describes the way our minds have evolved, and offers suggestions for how to cope with who we are in the world we live in now. Recent decades have seen remarkable progress in many areas. For example, while not overlooking the abject suffering of millions of people, it is nonetheless true that there has been unprecedented alleviation of poverty and disease for the world’s poorest people. There are so many promising and astonishing advances in medicine, technology, and the social and physical sciences that if we give ourselves a chance to survive, our species could enter a golden age.

How Life On the Savanna Shaped Our Minds

The mental machinery we’ve inherited makes it extremely difficult for us to understand, or even to perceive, our collective problems, let alone to solve them. These instincts evolved to cope with a different “world.”

Starting millions of years ago, and culminating perhaps 50,000 years ago, evolution shaped the human brain to detect and respond quickly to sudden changes in familiar and unchanging surroundings. Slow moving with a tasty appearance, and lacking claws and fangs, our ancestors’ survival depended upon quickly recognizing how a few subtle clues, like the crack of a stick or the sudden darkening of the cave entrance, might represent an immediate threat or a fleeting opportunity.

The need to develop quick thinking was intense; The chance to obtain much-needed food could disappear in an instant. A mistake in assuming that something was a threat had far less serious consequences than mistakenly waiting to see what might happen. Individuals on the savanna who were slow to act did not survive to pass on their genes, and quick action depended on developing rapid mental shortcuts. To detect sudden changes, our ancestors’ minds came to blend gradual changes into a static and familiar reality. This was functional, for little changed on the savanna over the course of a lifetime. There was no benefit to responding to changes that develop over decades, because there weren’t any, and life was short.

These “default settings” of the human mind worked well for thousands of generations. While obviously excellent in their own way, today these reflexes can lead to calamitous results when faced with conditions that did not exist when they were developed. Unlike our forebears, very few humans now face the day-to-day prospect of becoming something’s meal. Most children grow up without ever seeing where their food comes from, let alone hunting for it. We have changed the world to make our lives safer and easier. We were able to do so because we are not only the most intelligent animal, we are also the most cooperative.

Groups of humans working together can change the environment far more rapidly than individuals can. Agriculture, the rise of cities and civilizations, organized religion, writing, metallurgy, mathematics and science, printing, exploration of the globe, the industrial revolutions, medical science, modern communications, birth control, computers – all developed without any physical upgrades to the human brain. Our brains in fact have not changed significantly in at least 50,000, and possibly more than 100,000 years. Recent evidence suggests that if anything they are actually getting smaller.

There are obvious differences between an individual living in one of the few remaining stone-age tribes and a citizen of an industrialized nation. Those differences are due to differences in culture. An infant adopted at an early age from the tribal society and raised in the industrial world would grow to be a normally functioning individual, assuming an otherwise healthy situation. But cultures too have moved away from the environment in which they evolved. While the material benefits of large industrialized societies are obvious, humans evolved belonging to groups of perhaps 200 individuals. Most of us now commonly see more new people in a single day than our ancestors met in their entire lifetimes.

The very speed at which culture evolves, that is, the evolution of co-operative thinking, is much more rapid than biological evolution, but cultural evolution has been overwhelmed by its own power. Our collective activities have created the present day problems that our present day brains fail to understand. It is as if we are trying to run 21st century mental software on 50,000-year-old mental hardware. When under stress, our separation into like-minded groups all too often exposes the darker instincts we harbor as individuals.

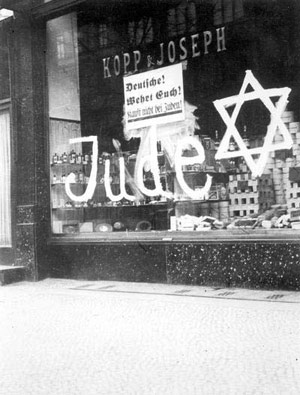

Caution that was prudent when meeting a stranger on the savanna can today become hostility when we are surrounded by so many who seem different. This tendency is especially great when we are faced with a possible shortage, a condition in which we are hypersensitive. At these times, a potentially competing stranger can become transformed into an object – an “immigrant” for example, or a “Jew” or a “Muslim” – something that seems to no longer be a flesh-and-blood person. One can treat an object in ways that our conscience would not permit us to treat another person.

The Problems of Our Mismatched Minds

NWNM surveys the evolution of our distant ancestors as the science was understood when the book was published – the origin of a variety of hominids in Africa, how climate change forced some of these creatures to move to the grasslands where they became bipedal, and the succeeding physical, mental, and social developments of Homo sapiens. This is the story of how our mind was formed, the mind we still possess. There are newer details in this story of The Human Journey, but today the basic elements are still the same.

Over millions of years, several distinct human species migrated out of Africa and spread around the globe. Eventually just one single human species survived. After the last Ice Age ended, the revolutionary transformation of the planet began with the invention of agriculture, the single most important event in the history of civilization. NWNM traces further developments forward through the Age of Exploration and the Industrial Revolutions to show how groups of humans have changed the world much faster than individuals can cope with the consequences.

Our primate brains fix easily on shiny objects, loud noises, and sudden movements. Because the things that distract us are more sophisticated than those that intrigue our primate cousins, we don’t see them for what they are. Our attention to these things is part of our “fight or flight” response. This response gives select stimuli fast access to consciousness. We ignore most information about the outside world so that threats and opportunities can be detected and responded to immediately. Perhaps only one trillionth of the natural stimuli that surrounds us actually makes it into our brains, let alone into our consciousness.

Humans can’t sense the Earth’s magnetic field, for example, as can robins. Unlike robins, this ability had no survival or reproductive value for humans. But we also lack the ability to detect phenomena that did not exist or were unimportant on the savanna but have now become so, such as radiation. And changes that are happening slowly still blend into what we call normal – the background that we use in order to contrast and detect sudden changes. The world has been growing warmer on average by about 0.02°C each year. Is it any wonder that many people don’t believe this is happening? But it is quite possible that this very gradual and ongoing warming might destroy the world’s agriculture.

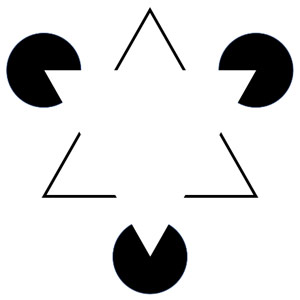

After filtering out the stimuli that are deemed irrelevant, we assemble what we do perceive into simple mental structures. We compose the world in our heads from perceptions that are allowed in. For instance, as infants we learn that certain combinations of shapes represent a person, a building, and so on. We are so good at this that we can identify a familiar face from a picture of just few gray rectangles. Our perceptual system attempts to organize things into meaningful patterns even when we know there are none, as when we find shapes in clouds. The world we perceive is actually within us, a shadow of the world that we inhabit.

The way we categorize perceptions is similar to how our senses limit them, and for the same reason, so that we can make quick judgments. One such example is that we categorize individual people into types, where everyone of that type is thought to be nearly the same. Again, back on the savanna the risks of not trusting the uncommon stranger were substantially less than being too trusting. Categorizing individuals can be helpful to a degree for those living in a homogeneous group of people. This mental shortcut works especially poorly in the new world, where every day, either in person or through the media, we encounter many people that appear different from ourselves.

And as we know, too many of us further assume that because of gender, race, or age, these strangers are not as smart, honest, or decent as we are. But more than this, we remember things about these people that are not true. Experiments by social psychologists demonstrate that after hearing descriptions of individuals who belong to a discriminated group, test subjects overlooked their individual qualities but recalled details that fit the stereotype. But more than this, they also “remembered” details that they had not heard, filling their memories with “information” that also fit the stereotype.

A good example of how an ancient and helpful shortcut can lead to error in today’s world is our tendency to arrange perceptions into patterns, and weave together experiences into stories. This is clearly important. But some of the mistakes this may lead to are: ignoring contradictory evidence so we can confirm our expectations, giving too much weight to anecdotal evidence, assigning motives to inanimate objects or natural occurrences, and misunderstanding probability (“heads has come up five times in a row, it’s got to be tails this time”).

There are of course people who exploit the limits of our old minds for their own benefits. NWNM was written 30 years ago, and some of its examples of leaders who take advantage of short-term thinking are likely unfamiliar to a new generation of readers. Nevertheless many of the examples in NWNM refer to the United States government. If anything, understanding old-mind thinking in this context is even more critical now. For all of its wrongdoing and shortcomings, for 75 years most nations of the world have looked to the US for leadership in dealing with the world’s problems. At this time, that leadership is controlled by the darkest impulses of old-mind thinking.

The Beginnings of Real Change

For all of our cognitive shortcomings and alarming problems, the authors of NWMW state that it is possible to change the way we think, to change the way we perceive the world, and to avert catastrophe. Humanity may eventually achieve an understanding of who we truly are, but we have no time to wait for “survival of the fittest” to help advance us forward. Natural evolution won’t work in our present circumstances anyway. We can’t fight a nuclear war and then decide never to do it again. We can’t wait for market forces to gradually phase out fossil fuels while global warming destroys the world’s agriculture.

Several factors set humans apart in the animal kingdom – speech, intelligence, memory – but perhaps the most exceptional difference is cooperation. We are possessed of a degree of empathy unmatched in the natural world. If we often see ourselves as uncooperative and uncaring, that is only because we fall short of the high ideal we have stored within us. Now we need to help one another to change purposefully and consciously. First of all, more people have to understand that we have set ourselves on a path that could destroy civilization. We need to change our educational programs so that they teach about our mental shortcomings. We also must be educated on how to use the excellent mental tools that we do possess to overcome those shortcomings.

NWNM suggests a curriculum to educate the new mind. A few of the suggested subjects are

- Human evolution, to understand the limitations and strengths of our minds

- Cognitive bias, to learn how our mental shortcuts can lead to bad decisions

- Probability, as a tool to understand likely outcomes and make better decisions

- Histories of societal responses to major threats, such as environmental change

NWMN also suggests methods that might be used to teach these subjects. Optical illusions, for example, are both entertaining and enlightening to demonstrate that our perceptions can be inaccurate and unreliable. Time lapse photography can be used to make it plain that we tend to ignore slowly-changing conditions. NWNM places emphasis on the possible roles that can be played by electronic media, computer games and simulations, and film. Literature for teaching professionals contains many simple (and safe) activities that can be carried out in a classroom setting to demonstrate how prejudices can develop in group thinking.

The suggestions in NWNM are not intended to be a prescription, rather they are intended to prompt readers to take part in developing solutions. Some of the suggestions, now 30 years old, are dated, and some are already being implemented. More recent insights inform possible new approaches. For example, Jared Diamonds’ Collapse recounts not only how some societies failed to cope successfully with serious environmental threats, but also how others did manage to overcome nearly identical threats.

Humanity On a Tightrope

Executives at the oil giant Exxon knew by 1981 that climate change presented a terrible risk to the planet. Exxon scientists were among the early leaders in uncovering and publicizing the dangers of global warming. Confronted with the research of their own scientists, these executives launched a campaign to discredit both the research and their researchers. They spent tens of millions of dollars to spread false information. These executives were not in the grip of old-mind thinking, failing to perceive a slowly developing threat. Quite the opposite – their campaign was designed to distract and dissuade people from that threat using knowledge of how to exploit old-mind weaknesses.

It is well established that it is possible to persuade people to act against their own best interests, for example by voting to make it more difficult to get medical care. In addition to climate change, similar deceptive campaigns target efforts to reduce income inequality, to lower population growth in the underdeveloped world, and to regulate guns in the United States. The people behind these deceitful campaigns are not making old-mind mistakes, unless greed is part of old mind thinking. They do suffer a great lack of empathy. About twenty years after publishing New World, New Mind, its authors addressed this lack of empathy in a follow-on book titled Humanity on a Tightrope.

Here Ornstein and Ehrlich explore how to restore the empathy that comes so naturally to our species. Empathy is not exactly the same as sympathy, although they are often taken as synonymous. Empathy is insight into what motivates someone, while sympathy goes further to also include a measure of compassion. But while empathy does not necessarily lead to forgiveness, it does restore an understanding that the other person, however different, is a human being. Empathy can be increased by some simple and pleasurable actions. A thought-provoking movie can show us how everyone is much like us. A walk in a place of natural beauty can restore a sense of awe.

But much more is needed. We are organized into giant “us-them” groups where our old world instincts are being slyly manipulated for the benefit of a few. This is a huge problem, and action must go beyond any steps individuals alone can take, important though these are. We must demand more of our institutions. It is especially important, given the state of today’s media, to process news more thoughtfully, while avoiding the “naïve cynicism” that many people use as a substitute for judgment. Our old world brains ignore slowly developing good news as well as bad. This may cause us to miss opportunities to which we can make a positive contribution.

We are all genetically, socially, and environmentally related. We must replace the threats that we imagine come from “them” with an understanding of the threats we pose to ourselves. That understanding must come both from our formal and informal education. All of the world’s great religions declare that people can be best seen as brothers and sisters. This is a metaphor for the true condition of humanity. We need a new synthesis between modern scientific understanding of Homo sapiens and this essence that lies at the heart of genuine religion.

Robert Ornstein was the author of more than twenty books, among them The Right Mind, The Evolution of Consciousness, and the best-selling The Psychology of Consciousness, now in its 4th edition. His final book, which he considered his most important, was the groundbreaking God 4.0: On the Nature of Higher Consciousness and the Experience Called “God.” He was the founder of the Institute for the Study of Human Knowledge, which is responsible for this Human Journey website. (See also: www.robertornstein.com.)

Thinking Big

How the Evolution of Social Life Shaped the Human Mind

Robin Dunbar, Clive Gamble & John Gowlett

The social brain that drives our behavior and contemporary culture is essentially the same brain that appeared with the earliest humans some 300,000 years ago.

Social: Why Our Brains are Wired to Connect

Matthew D. Lieberman

Explore the groundbreaking research in social neuroscience revealing that our need to connect with other people is even more fundamental, more basic, than our need for food or shelter. Because of this, our brain uses its spare time to learn about the social world – other people and our relation to them.

Moral Tribes

Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and Them

Joshua D. Greene

Our innate moral behavior evolved over millions of years to promote cooperation within our group. Each group has its own moral code, which provides a map for how individuals can live successfully within it. Our other innate tendency, to favor our group over all others, is something we need to understand and mitigate to address the existential challenges of our modern global society.

The Righteous Mind

Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion

Jonanthan Haidt; reviewed by John Zada

We are without doubt living in an era of polarised thinking, marked by much bickering across social and political lines. But could positions of both side have roots in common moral foundations?

The Mountain People

Colin Turnbull

The story of the IK tribe of northeastern Uganda is a classic study of how a society’s concept of fairness and justice can quickly devolve when its people are cut off from their accustomed means of livelihood and forced to compete for their very survival.

Multimind: A New Way of Looking at Human Behavior

This provocative book challenges the most-popularly held conceptions of who we are. In it, psychologist and renowned brain expert Robert Ornstein (1942 – 2018) shows that, contrary to popular and deep-rooted belief, the human mind is not one unified entity but, rather, is multiple in nature and is designed to carry out various programs at the same time.

Humanity on a Tightrope

Paul Ehrlich & Robert Ornstein

Psychologist Robert Ornstein and biologist Paul Ehrlich join forces to explain why the human race has reached its current perilous precipice. To sidestep the fate they say is now barreling towards us will require us to address our “empathy shortfall.”

The Matter with Things

Iain McGilchrist

One of McGilchrist’s central points is that our society is one in which we rely on representations of the world as our way of knowing it. Scientific theories expressed in mathematical form, economic models, photographs – all re-present the reality they purport to describe.

Beyond Culture:

Edward T. Hall and Our Hidden Culture

Report by John Zada

Edward T. Hall, after spending his early adulthood working and travelling among non-Anglophones, both in the United States and in other parts of the world, became cognizant and fascinated in the deeper layers of culture that he claimed lie buried beneath those more obvious forms.