Featured Book

The Business of Changing the World

How Billionaires, Tech Disrupters, and Social Entrepreneurs Are Transforming the Global Aid Industry

In 2000, Raj Kumar and friends created Devex, an online community for global development that matches up organizations with funding opportunities and provides the largest database of grants, tenders, and other funding information. This book was written 20 years later to provide a clearer picture of how the industry operates, and the emerging trends in global aid.

Giving is increasingly being evaluated not by the goodness of the intentions or the amount of money given but rather by results. There’s a major shift toward seeing aid recipients as “customers” of aid instead of nameless, voiceless “beneficiaries.” And this shift depends on “customer feedback.”

The phenomenal growth of internet connectivity, biometric identification and mobile banking enables anyone anywhere to reach the world’s poor directly. That technology has allowed organizations to gather real-time results on what is needed, who needs it, and where it is needed, and, almost more importantly, whether the funds provided actually work to fix the problems.

Changing “The Colonial Mind-Set”

–Kumar recounts how the traditional aid industry operates from the “top down” model stemming from the legacy of colonialism. Donors had the say-so on how the programs would be implemented, how “their” money would be spent. Kumar and others have posited that this “monopsony” way of thinking will need to change if the world wants to eliminate extreme poverty.

The US food aid program, for example, will only allow food to be transported in US-based vessels, something called the “cargo preference rule.” Kumar says, “The use of an old fleet of US vessels specifically for this purpose means shipping costs that are 46 percent higher than they would be if shipped at international competitive rates, and shipping times that can be up to fourteen weeks longer.” The food given out by the US must also be “Made in the USA.” This is not, Kumar explains, a results-oriented approach that would prioritize saving lives and creating sustainable domestic agricultural markets.

Many aid programs have come and gone due to political interference. US senator Jesse Helms famously alleged, for example, that aid was going down “foreign rat holes.” Effective programs inside Afghanistan were stopped simply because of the insistence on “accounting for every penny” – an unreasonable requirement in that war-torn country.

The Bush and Obama eras ushered in some important change of thinking that led to US foreign aid more than tripling in the past two decades. Globally, countries such as China, South Korea, Australia, and Turkey, have also developed and expanded their aid programs. But, Kumar says, “Even with all this change and advancement, much about the aid industry remains the same. Most USAID funding still goes to a small group of American NGOs and contractors, and the same is true of funding from the British, French, Germans, Japanese, Australians, and so on. Preference is still given to NGOs and aid contractors from the donor country. Most major aid projects and organizations are still led by Americans and Europeans. The old model of rigidly designed ‘projects’ still persists.”

What Kumar calls “The Colonial Mind-Set” has produced a whole vocabulary in its resistance to changing how aid is provided. The word “aid” itself is antiquated, denoting a savior from above, rather than people helping themselves out of poverty and strife. The word “ex-pat” refer to residents who migrated from rich countries and “locals” or “migrants” refer to the poor in the recipient country. The term “appropriate technologies,” euphemistic for spending less on medical devices or drugs for poor people, is still in use today, a sign that the old “colonial mind-set” is engrained.

But it is not necessarily an unbendable mindset because today we are asking “fundamental questions about why we do this work and how we can reach seemingly impossible goals, like the end of extreme poverty.”

The Billionaire Effect

Forbes lists more than 2,400 billionaires all over the world, a small group that is often cited as having more wealth among them than the rest of the world’s population. That’s an enormous amount of wealth in the hands of a few who are under increasing pressure to put their resources to work for the common good.

Using examples of a small group of billionaire funders, Kumar outlines the varying styles of philanthropic endeavors they are backing and how they are making their mark and changing the old mind-set.

Good Ventures was started by two young Silicon Valley executives and is, says Kumar, a “cutting-edge foundation which represents the future of global philanthropy: wealthy, committed, and personally engaged donors with a results-oriented, Silicon Valley-style approach.” The founders have vowed to give away all their wealth in their lifetimes.

To help with problems that are time-critical and cannot wait until funds are delivered by the old way of thinking, billionaire philanthropists Warren Buffett and Bill Gates started The Giving Pledge. Along with George Soros, Michael Bloomberg, and more than 200 others from 23 countries, they have signed on “to commit more than half of their wealth to philanthropy or charitable causes either during their lifetime or in their will.”

Issues taken on by these billionaire philanthropies include projects for anti-smoking, road construction, ending child marriage, treating and ending non-communicable diseases such as diabetes, as well as infectious diseases such as malaria, polio, AIDS, Ebola, and now deadly coronaviruses. These types of projects are very attractive to funders because investments can be easily measured mainly because of the scale of the problem.

Some of these contributions are made to multilateral aid organizations such as The World Health Organization (WHO). The Gates Foundation’s donations to WHO, for example, are greater than those of every country in the world except the United States. The foundation has highlighted only “data-driven” projects, an idea they are pushing for the entire aid industry.

Some billionaires are launching and operating their own entities, such as Mark Zuckerberg and Cheryl Chan’s CZI initiative, that require building large in-house staffs and implementation teams and have no public transparency – something that may one day have to change.

Jeff Bezos of Amazon has given hundreds of millions to charity and pledged $2B to programs for the homeless and early childhood education. But he has not taken the Giving Pledge, and has been criticized for it. (As of April, 2020, Bezos’ net worth is said to have increased by $24B during the coronavirus pandemic).

“It’s Big, but is it Good?”

“As much as billionaires might like to think of their giving as an unalloyed good, their philanthropy will increasingly be a subject of controversy and a political issue itself,” says Kumar.

Liberia, for example, is a country with an extremely high rate of out-of-school children. A major schools project called Partnership Schools for Liberia (PSL) (now The Liberia Educational Advancement Program, or LEAP) became highly politicized on issues of private versus government schools in poor countries, due in part to the fact that some of the reformers backing the initiative were billionaire philanthropists. This is also a concern among many educators in the US. Billionaires are able to avoid taxes by putting their wealth into their own private foundations, which in turn support private, for-profit education providers. Funds are thus diverted away from a strong public school system.

Tax, regulatory and finance reform is a growing concern with the coming wave of billionaire philanthropy, especially in the US. There is the point of view that increased reliance on billionaire funding puts too much decision-making in the hands of a very small, unelected, and not necessarily qualified group of already too powerful individuals. Some economists believe that no amount of billionaire funding can solve the underlying issue: the continued exponential growth of income inequality. Beyond taxation and finance reform, a fundamental global economic restructuring including massive debt forgiveness will be the only way to ultimately rid the world of extreme poverty.

Nevertheless, this is where we are – where the money is – and the needs remain. Kumar asks, are these political and ideological concerns going to lead us toward a more results-oriented philanthropy and holding billionaires accountable when their giving isn’t generating or even targeting the results the world needs?

Many well-meaning, but “old mind-set” donors began programs in the early 2000s when results were given little or no consideration. As an example, Kumar cites Nicholas Negroponte’s “One Laptop per Child” (OLPC) initiative that planned to deliver 150 million crank-powered laptops to children in developing countries by 2007. Uruguay and Peru placed large orders, but due to the lack of teacher training, technical support, or even any measurable positive impact on learning, the laptops ultimately fell into landfills or the hands of unscrupulous parts dealers.

Had there been a “results-oriented” approach, a preliminary study would have demonstrated that laptops actually improve literacy. Teachers would have been trained, technical staff provided for programming and repair, and a plan put in place for recycling. There would have had a tiered roll-out and perhaps even a focus on manufacturing the laptops in the area where they were to be used.

As contrasting example of success, Kumar cites the Kenyan “Zusha” program for controlling road accidents. The program was well-researched and a low-cost sticker for road signs was developed that resulted in a drastic reduction in deaths.

Many of the most successful results-oriented programs are in global health: fighting meningitis A in sub-Saharan Africa and guinea worm disease from fleas in drinking water that affects millions in countries all across Africa and Asia, and the near eradication of polio. One of the greatest success stories of the past few decades has been the slowing of the spread of AIDS in under-developed countries, as well as the development of effective treatments for the disease, which has already killed over 35 million.

Misplaced Motives: Donors Want to Feel Good

A big cause of misplaced giving is that many people, donors large and small, make their decisions based on what makes them feel good without seriously considering the real impact. Donating for and enabling orphanages is the classic, and sadly still pervasive example.

Writes Kumar: “According to the United Nations, some 80 percent of the 150 million children living in orphanages today actually have living family members, including at least one parent.” He points out it actually costs more to fund orphanages than it would to give parents the money they need to care for their own kids.

Studies have shown that some orphanage programs are run by unscrupulous types, giving rise to some of the most egregious acts against children, including child slavery, starvation, and sex trade. This not only harms the children, but also acts to exacerbate extreme poverty. But donors love orphanages!

Some countries and agencies advocate eliminating orphanages entirely for children where there are viable family members around. With that option, programs must first be in place to reduce poverty and ensure families can survive with extra mouths to feed.

This raises the issue of focusing on the right success metrics. In the early 2000s, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were conducted to determine the impact of giving deworming pills to kids in school. The study showed that a pill costing pennies could have an enormous impact in fighting global poverty. Ten years later another RCT revealed errors in the original study that had resulted in a dramatic overstatement of the potential outcome. The result was the infamous “Worm Wars.” Economists entered heated debates over continuing the program, which thankfully remains in operation; whatever the impact on poverty reduction, the program continues to saves millions of lives.

Says Kumar, “So philanthropists now have to ask themselves: should I take the risk on the long-term investment or fund something that we know works and can reach huge numbers of people immediately? Whatever the answer, what matters is asking the question.”

Guidance for Impactful Giving

Kumar offers a brief checklist for aid workers and organizations to help avoid mistakes of oversimplification or succumbing to the draw of good intentions. Ensure the project or organization has:

- A clear definition of the success factors being measured (e.g., literacy rates or incomes or maternal deaths or reduction in conflict or human trafficking)

- A logic model, explaining in very concise form the theory of how this intervention is going to move the needle on those factors being measured

- A listing of risks to the very people you’re trying to help: what could go wrong that would actually hurt them?

- A listing of risks to others: could there be unintended consequences for others in the community or the family?

- A projected cost-benefit ratio

- An itemized list of the data points that will be tracked and publicly released (along with information on how often each will be released)

- A statement of how lessons learned will be shared and acted upon (and how often)

- A checkbox on sustainability: whether the project or initiative aims to be sustainable over time by generating its own source of funding or through transfer to a national government or local institutions, and, if so, how

Innovative Funding Mechanisms

The entrance of billionaires, tech innovators and entrepreneurs have had other impacts on the aid industry, introducing whole new funding models such as the “social impact” and “development impact” bonds, specifically designed to attract private capital to fund global development goals. Investors agree to take a risk on a development project in exchange for a payoff if it succeeds. Says Kumar, “Instead of telling aid organizations precisely what to do, these bonds let the NGOs do their own thing: try, experiment, make mistakes, and try again. They’ll stay laser-focused on the end results rather than try to execute a plan designed thousands of miles away.”

In Rajasthan, a state in northwest India where almost 5 percent of babies born alive don’t survive, two highly regarded NGOs – Population Services International and Hindustan Lever Family Planning Promotion Trust – were tasked to find ways to improve maternal and newborn care. If they are successful and hit their targets, they’ll get paid what it costs to do the work plus a success bonus by USAID and Merck for Mothers.

These bonds are instruments that basically try to pay for results while spreading the risk around. Says Kumar, “The beauty of this model is that there’s lots of investor money out there, far more than there is philanthropic money. Think trillions rather than billions. Rather than risking philanthropic grant money up front, in this model it’s investor money that’s at risk. Only if the results are achieved do the donors pay. … By 2018, the World Bank was announcing a Famine Action Mechanism that front-loads funding to countries where famine is predicted using advanced analytics tools. Partners in the effort include Amazon, Google, and Microsoft. There will still be a critical need for philanthropic money, and there’s much more of that flowing now. A tidal wave of billionaire and ordinary giving is coming. DIBs and other innovative financing mechanisms could mobilize that funding and make it far more effective.”

Another innovative funding mechanism, the “Global Financing Facility” is designed to get middle-income countries to invest more in healthcare. In 2016 the World Bank created a cheap-loan mechanism for countries faced with a sudden influx of refugees, such as Jordan and Lebanon. In 2017 the bank issued “pandemic bonds,” a kind of insurance scheme designed to pay out to countries hit with an outbreak of disease (at the time it was Ebola). And now they have a “Famine Action Mechanism” on tap.

Unintended Consequences

There is a danger in results-oriented funding, Kumar believes, “that we’ll prioritize what is easiest to measure. …The danger in focusing only on wholly tangible results is that it provides an opening for aid opponents with isolationist, us-versus-them agendas to criticize work that’s essential but more difficult to measure.”

Kumar is optimistic that results-oriented programs will win out, though, and very soon. However, he does warn about a “shakeup” in the funding industry. Traditional NGOs could be in for a rude awakening, he intimates, if their cultures and approaches do not embrace this new “bonding” of results to make or break a funding idea. Some NGOs and funding institutions are too large to fail entirely, but old-era entities will be forced to change in order to adapt in the “new era” where it’s “the ultrapoor, not your largest funders, who are your key customers.”

In 2015 the World Bank created a Mind, Behavior, and Development (eMBeD) team of about a dozen behavioral scientists. The behavioral science approach sometimes uses a tool called “human-centered design” (HCD). This tool or procedure directly engages with the people who are to be served. This HCD information turns recipients into “users” rather than “the needy,” and they are considered as “customers” with a voice in their own well-being.

One way that the country of India thinks might help is the Aadhaar program, a massive effort to biometrically identify all the country’s 1.3 billion citizens by cataloguing fingerprints (if one hasn’t lost their fingerprints due to hard manual labor) and irises, and to use this data to determine where social service support is most needed. Is this too “big-brother”? Are there negatives? Sure. Kumar cites among the downsides the potential for political destabilization (splitting the country into “haves” and “have-nots”), cultural loss, especially to the younger generation in the areas served, proliferation of scams, and consumerism, among others. Mega connective companies such as Google, Facebook and Microsoft don’t think of their products primarily as being used in humanitarian activity, but as being a part of their business model. Yet connectivity will be a key part of transforming how the aid industry works.

Helping with Cash

What about cash to recipients to help end poverty? Kumar includes a discussion of low-finance tools and the use of easy connections for getting cash through modern technology. The Kenyan mobile money platform M-Pesa allows people to transfer cash to family and friends and buy health and other insurance policies. M-Pesa started with telecom company Vodafone and UK’s DFID. The Gates Foundation has funded several others such as Cellcard in Cambodia, Digicel in Fiji, Orange in West Africa, Safaricom in Kenya, Tata Indicom in India, Telenor in Pakistan, and Tigo in Africa.

Says Kumar, “At the very least, it will be more efficient to get money from friends and family using systems like M-Pesa. The days of loan sharks and money traders controlling the financial stability of the world’s poor are numbered.”

“Every country, every business, every village chief, even every family should have their own crisis plans.”

When a disaster hits, the expansion of mobile cash will be important. Just handing out cash at “ground-zero,” for instance, invites corruption and most of it would not go to those in need. Humanitarian aid in the future would be far more efficient using mobile electronic cash transfers, and it would certainly be less expensive than shipping bags of grain across the ocean to a disaster area where ports and distribution may not even exist. Of course, issues of privacy and data security would need to be sorted out well in advance of the disaster, which means studies showing what data needs to be collected and how to keep it secure during and after a disaster hits. In addition, staffing would have to be in place to interpret this data and help design the best approach to assistance. [Editor’s note: This is a consideration that is on the immediate horizon in the aftermath of the coronavirus pandemic, in terms of both controlling the spread of the disease and responding to food insecurity.]

Says Kumar, “Every country, every business, every village chief, even every family should have their own crisis plans. Thinking through what to do in a time of crisis—alongside the best practices from the world’s leading NGOs and humanitarian agencies—can lead us down the path to a future where emergencies are less destructive and communities can bounce back faster.”

Changing the Culture

Using the new ideas of results-oriented programs can also support massive “cultural change” needed in many places globally to keep humanity on the road to well-being. Kumar cites the example of child (“forced”) marriages in India. The country now has laws in place to help stop this practice which have produced the demonstrable result of girls getting more education and waiting longer for child-bearing. Programs such as the Save the Children offer free cooking oil for as long as a girl remains unmarried or cash subsidies to families for unmarried girls in a household. “Their families begin to see them as ‘assets rather than liabilities.’”

Big Business as a Social Enterprise

Today, says Kumar, both NGOs and corporations must also “think about their commitment to the ‘social contract,’ the term coined by the eighteenth-century political theorist Jean-Jacques Rousseau essentially meaning a commitment to shared purpose.”

Patagonia’s “shared value” concept – that businesses must focus on value not just for their shareholders but also for their community at large – goes against the hard-set view of many economic rationalists that corporate value is measured by ever-increasing growth in financial return.

For businesses to adopt “shared value” concepts, they will, of course, have to abide by the rules and laws of governing agencies, and also pay attention to benefiting employees, communities and society. They will have to “rethink their purpose.” Nike and other companies, for example, have come under fire for dependence on slave wages to meet their bottom line. These companies must take decisive steps to ensure wage increases and improvement in working conditions.

Companies that adopt the shared value concept cite research showing that consumers do care if a brand is known for taking good care of its employees or is a conscientious steward of the environment. S&P 500 companies showcase their environmental and social commitments. Kumar defines this as a “virtuous cycle:” activism calls out bad behavior and companies change to social entities behaving well.

“Not only do millennials not want to buy from brands that don’t have a social mission,” says Kumar, “they don’t want to work for companies that don’t have a social mission.”

Today, stockholders are also interested in “positive impact investing” through “socially responsible investment” funds (SRIs). Unfortunately, uneven tracking and review of these funds can lead to holding stakes in companies involved in major environmental disasters, unfair labor practices, or sexual harassment. Better screening is needed, Kumar contends, to more accurately report environmental, social and governance impact in a way that makes it easier for people to make good, smart decisions about their investments.

The next-step benefit of positive impact investing would be that companies begin to make products and services aimed at the poorest of us. Kumar says that the idea of the “ultrapoor” being valuable customers isn’t a new one, citing C.K. Prahalad’s The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: because there are so many at the bottom, small purchases add up to immense profits. Yet very few companies market to the poor, possibly because it requires producing high volumes of goods that can be sold at the low prices the poor can afford. There are, however, some successful programs aimed at the bottom of the pyramid.

Individuals as Social Entrepreneurs

Four MIT economics students formed Give Directly, an organization that identifies poor people and electronically sends each household a relatively large amount of money, such as $1,000. How do they find the poor? One way is by taking satellite images of houses with thatched roofs in areas that are known to have a high proportion of poor inhabitants. The program is proving transformative. “Customers” have an online feedback tool and give unvarnished stories of what the money means for them. Sponsor-a-child programs operated by big charities have been around for decades, says Kumar, but this is different. It’s more authentic, transparent, and direct.

New Story of San Francisco came up with a dynamic new algorithmic tool that has enabled construction of quality houses for poor people for around $6,500 each by contracting with local builders, not volunteers. This online tool matches the job to the builders and suppliers, and then puts the project out for online donations. Small crowdsourced donations add up fast, and the homes are built. By comparison, the American Red Cross collected $500 million to help rebuild Haiti after the 2010 earthquake and only managed to build 6 homes. The remaining cash went to services for the poor, but that’s not what the “customer” needed.

Global Giving, the world’s largest crowdsourcing platform for donations, allows people to donate directly to a specific project run by a local nonprofit. Other crowdfunding models have emerged around narrow issues. Charity: Water, for example, focuses on clean drinking water, and has raised close to a half billion dollars from small (and large) donors to provide clean drinking water to over 8 million people.

These models have one great advantage over the traditional NGOs with their many bureaucratic layers and immense long-term projects: the “retail” aid model can quickly scale to bring down costs and build up capital. The real issue is not one of scarcity, as is proven by the billions and even trillions raised for socially responsible programs by such donors as the Zuckerberg-Chan CZI Initiative, and by ordinary people loaning through microfinance platforms. There’s enormous potential to tackle some of the world’s biggest problems, including extreme poverty.

Crowdfunding doesn’t depend on richer countries investing in poorer ones. It creates the opportunity for anyone, even the poorest in a region, to give out of their own pockets toward basic necessities, such as a toilet. Also, as Kumar says, “Maybe it’s not that some people are too poor to afford a toilet but rather that toilets haven’t been designed to be affordable. This shift in thinking is critical to the new world of aid we’re in today. The old worldview sees poverty as an immovable object; the new one, in which poor people are consumers, sees poverty as another business issue to be overcome.

Kumar is optimistic that the aid industry will eventually become more “wholesale” minded, where more projects are aimed at balancing the main objective with a more direct connection between the person giving and the person consuming the aid. Ordinary donors have choices, are able to understand value and to know what they’re actually “buying” with their money.

Open Source Aid

In the early 2000s, AOL founder Steve Case and his wife, Jean, as well as former First Lady Laura Bush and others, invested in PlayPumps, a failed low-tech innovation in which children pump drinkable well water by playing on a merry-go-round. Why did this failure deserve a mention? Because, says Kumar, the funders learned that it was failing and shut it down. They didn’t just stop there, they openly acknowledged the mistakes and applied what they had learned to better, more effective initiatives. And, Kumar hopes, this sort of “creative destruction” will become more common in the “new” aid industry.

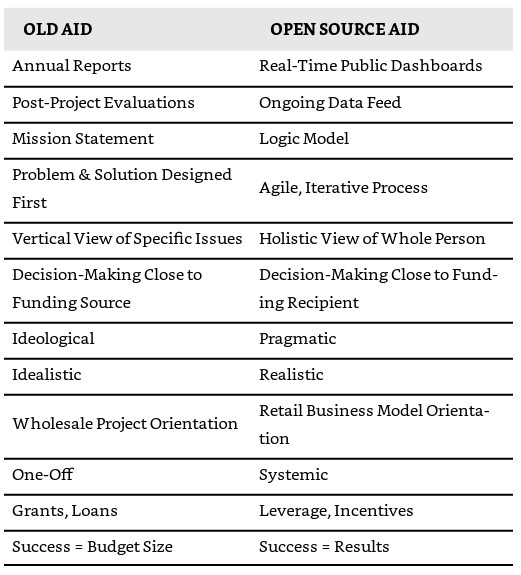

What Kumar calls “open source aid” will be a “combination of having the humility to assume no charitable idea is going to work out exactly as intended and the honesty to share experiences and results, good and bad.” He provides a chart comparing old aid thinking with open source aid to illustrate his thoughts:

Open-source aid values contributions by everyone, from the CEO to the poor person who provides feedback. This process assumes, as Kumar writes, that “all lives have equal value and saving as many lives as possible should be our goal.” GitHub, an open source online platform for web developers, and Wikipedia, an open source for information on any subject, are two examples of the direction open collaboration can take us.

As the aid industry has begun to focus more on evidence and results in designing their funding, tools such as the XPrize and Grand Challenges Canada and other competition grants are cropping up.

“What’s incredible about competition grants is their efficiency,” writes Kumar. “Given the causes involved, many people are willing to contribute their ideas and efforts without receiving a paycheck. Participating in a competition to solve an important problem is its own reward. Plus, using a tiered model allows funders to experiment with innovative ideas while reserving significant money for ideas that are proved and ready to scale.”

One example is the Global Innovation Fund (GIF) that invests in rigorous testing of innovations to improve the lives of the poorest people in developing countries. Small grants are used to determine what works, such as connecting global corporations with refugees with skills they need.

What Kumar labels “effective altruism” is part of trending emphasis on saving large numbers of lives rather than gleaning extraordinary profits. Some say this focus on evidence can fail because it is disconnected from the very people it is trying to save. It doesn’t take into account the political and social history of a region in need. Large foundations such as Oxfam, the Gates Foundation and the World Bank have learned the need to focus not just on short-term needs, but long-term support for civil society, good governance, and peace. Yet, some projects can’t wait for fundamental social changes. The need is too urgent.

Problems of Transparency

China is one of the major donors toward global aid, seeing it as a direct extension of its foreign policy. China does not fund large foreign NGOs, but instead uses Chinese companies to set up the infrastructure needed for aid projects. But with no reporting mechanisms in place, almost no data on its programs exists.

A banking institution called Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) was set up to oversee these infrastructure projects, and in recent years some large Western countries have become affiliated with the AIIB (although, not the US). These affiliates are hoping to push the bank to adopt the same kinds of environmental and social safeguards as the World Bank has had to take on.

China illustrates the main obstacles to open source aid: (1) most aid currently comes from government contracting and (2) large-scale procurements can only be done by central governments. The USAID and other agencies will have to figure out how to take more risks and come up with solutions with private companies and online communities, and they will need to move more quickly. Who would have thought the future of the world, including critical challenges like ending global poverty, would be in the hands of procurement officers?

Systems Thinking: Embracing Complexity

Identifying complex global development problems is not an easy task because they connect to history, politics, and culture. Kumar tells the story of visiting Myanmar in 2015: “One of the world’s last closed-off countries – a pariah state of over fifty million people strategically situated between China and India – could soon be thrust onto the world stage and its people could jump on a fast-rising wave that would propel them out of poverty and into modernity.”

International NGOs had been entirely banned from Myanmar for five decades, and there was no development community in place. Laws on property ownership were never enforced for poor farmers; a military officer could simply appropriate a farm just by moving the farmer out and taking the land. These poor farmers had very little recourse. A grassroots organization of “barefoot lawyers” arose which trained farmers in the rule of land ownership, and little by little some farmers were able to reclaim their property. This process didn’t require a large budget. It was something simple, based on what local people needed and an understanding of human behavior.

But can such simple grassroots changes work in places where there are entrenched ethnic divisions? In Myanmar, the Rohingya have experienced years of persecution – a situation which has escalated since the country’s transition to democracy, with over a million living in the one of the world’s largest refugee settlements in Bangladesh. Kumar writes, “Ethnic divisions are too strong and democratic principles and institutions too weak to automatically prioritize growth and development for all citizens.”

Health Care as a System

Global health care is an example of daunting complexity. In conjunction with the WHO, Partners in Health (PIH) has become the largest, most impactful global health NGO. What was PIH’s radical idea? To put the patient first.

It’s at the community level where 70 percent of preventable deaths happen, so it makes good sense to focus there. If communities are empowered to build smaller clinics, train local nurses and health-care workers, patients could be served as needs arise. These local clinics could be connected to larger hospitals and transportation provided when the need arises. As daunting as it sounds, PIH was able to do it, and the organization has grown to the point that it can now draw on the advantages of scale to cut down on cost.

Many in the global aid community question how we can applaud hospitals for the elites and middle class when most people barely have access to a functioning health clinic. But Kumar regards this thinking as the old “us” vs. “them” view of aid. “If you design it right, you can leverage the market created by rich and middle-class people in order to expand services to the poor.” The high-end of the market can attract investment from private operators for building hospitals and clinics and training medical workers. These private operators don’t care who pays them – the government or aid agencies – but they know they will have to deliver better healthcare in order to get paid.

How would the poor afford such improved care? “That’s where a combination of government funds, private insurance, and wealthier patients come in,” says Kumar. And all this depends on well-intentioned aid agencies focusing on providing even the poorest patients with the most basic care in order to build a “market” as well as building good health for all. Of course, this vision of a market and its growth won’t come about in some poor regions without philanthropic aid, but it affords the “virtuous cycle” to begin.

Education as a System

Like health care, education also needs to apply the principles of local-level solutions. The program Teach for All focuses on building up local leaders with real experience in education. It sees thousands of local leaders prioritizing education in their own communities and thereby eventually over the entire system in their country.

The US also has its regions of low income and poverty where school systems are struggling not only to educate their kids but also to stay afloat in the ever-increasing divide of the “haves” and “have-nots.”

What’s at play here is the citizenry wanting a good education system for their children; community leaders who agree and want to choose systems that don’t harm the children and families; teachers and their unions wanting good education but not at the expense of the lives of their members; and finally, a government with fiscal constraints. Therefore, what is needed is a systems way of thinking and an understanding of behavioral dynamics.

Says Kumar, “That’s why three threads—systems thinking, behavioral science, and human-centered design—are today at the forefront of a new approach to global development challenges like education.”

The System of Governance

Governments can pose the most complex challenges to effective aid. In the Philippines, there is a president who has actually admitted to murder, masses involved in “people power” marches, and government-tolerated (even sanctioned) mistreatment of other political groups. In other countries, there is war and conflict, forced migration, and human rights abuses. How can the new aid industry even get a foothold in this world?

“The idea of paying for performance is beginning to catch on as one way to really target aid dollars to a specific result without necessarily propping up a corrupt government or unwittingly taking sides in an ethnic conflict,” writes Kumar. This should pay off, he thinks, although slowly and only by working with good governments where possible, and working around the bad ones.

The Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), formed in the George W. Bush administration to be outside the State Department and USAID, uses market principles to apply aid principally aimed toward infrastructure in countries which score well on basic measures such as fighting corruption and investing in health and education. The MCC model was slow in getting off the ground, hampered by “loopholes” allowing the Chinese to outbid all other providers and take over some projects. After closing some of these loopholes, MCC is now considered an effective and thoughtful approach to foreign aid. The World Bank has even adopted the MCC model for their Human Capital Index that scores countries based on how well they are doing to improve the health and education of their people. High-performing countries might get financial benefits such as cheaper loans; those who are governing poorly could pay more.

Absolute Zero

Kumar writes: “For the first time in modern human civilization since the dawn of the agricultural revolution, we may soon reach a tipping point in which the world remains fundamentally unequal – with billionaires and people just making ends meet living side by side – but where almost no one is born without their basic human needs being met.”

How can we get to zero absolute poverty? Kumar believes the answer lies in moving to the era of open source aid and gathering data on who is doing what, what is working, and what is not. This real-time data will become critical for all sorts of development work, he says, from education, to job creation, to water and sanitation, to fighting infectious diseases.

“For the first time in modern human civilization… we may soon reach a tipping point… where almost no one is born without their basic human needs being met.”

“Real-time data will allow a secondary market to develop. That would mean a private funder could create a bond that pays out when a development project succeeds and then sell that bond before the project is completed. The pricing would be based on how the project is going. This opening up of a larger secondary market for development impact bonds (and other kinds of impact investments) will ultimately attract more money to global development and help to fill the financing gap required to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.”

A second, and related, step in the quest to end extreme poverty is holding billionaires accountable. Traditional foundations will need to be rated and ranked by their results, called out for failures, and held to high standards by independent boards.

Even with these fundamental changes to the global aid philosophies, a more efficient system won’t solve the global challenge entirely; there are too many countries in conflict and too many human rights problems. Advocates need to help push governments to ramp up humanitarian responses within their countries. They need to call attention to effective migration from outside as well as from within their countries to help break the cycle of poverty.

However, today, walls and fences are the political tools in the West, and clan identity and segregation are on the upswing among Buddhists in Myanmar, Hindus in India, Muslims in Indonesia, and Christians in many African countries. Religious rights and marriage equality, not only for women but also LGBTQ people, need to be addressed in order to meet the goal of ending poverty by 2030.

In the face of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic and predicted crises of global warming, one of Kumar’s statements seems especially appropriate:

“In parts of the world with so few doctors, the focus must be on training up more community healthcare workers and equipping them with technology that makes them more effective. This will almost certainly include the ability to conduct sophisticated diagnostic testing on site using a smartphone and using AI tools to prescribe medicine based on the results and reported symptoms.

Making the global aid changes he advocates might eventually eliminate extreme poverty, but we will still be living in a deeply unequal and divided society where the lower end of the income scale cannot see their potential realized. Even if in the next few years some foundations reach their goals, such as the Gates Foundation and Rotary International goal of eradicating polio, there still will be the need to redirect global health spending toward the next urgent need as illustrated by the coronavirus pandemic.

However, Kumar warns: “Let’s not forget that rich countries are not yet even meeting their own targets for foreign aid spending, so talk of ending aid is far too premature.”

What Can We Do?

When mega-billionaires make donations to their alma maters or for building new arts centers, they are criticized by many for ignoring “real” problems that are so under-funded. The author posits that if organizations such as CARE were to get large donations, they would have to double their staff, double the scale of the programs, and be ready to connect with so many more countries and sectors in order to use that funding effectively. And foundations know this, which helps to explain why financier Warren Buffett gave most of his philanthropic money to Bill and Melinda Gates.

Kumar offers this list of recommendations for what the average individual can do to help make their donations work toward the common good:

(1) Make donations only to organizations that either show you rigorous data that prove their interventions work or that can make strong, logical cases for their expected impacts.

(2) Punish organizations that exploit images of children as victims. Donors should think only about empowering children with healthy lives and education.

(3) Don’t punish organizations that admit and learn from failures.

(4) Ask tough questions about the results the organization is achieving, rather than whether you simply “believe” in its feel-good causes.

(5) Explore crowdfunding opportunities for your cause.

(6) Consider supporting organizations—they can be nonprofit or for-profit—that are using technology and market mechanisms to empower people.

(7) Push your representatives in government to support foreign aid.

According to their mission statement, the U.S. Global Leadership Coalition (USGLC) is a nonprofit organization “formed by a coalition of American businesses and NGOs, senior national security and foreign policy experts, and faith-based and community leaders from across the United States who promote increased support for the United States’ diplomatic and development efforts among both politicians and the public.

The coalition argues that foreign aid is essential to homeland security. Their aim is to keep foreign aid nonpartisan and to ensure we consider how aid dollars are spent in tackling the biggest global challenges of our time.

Finding a job in the global aid market at one time was a simple matter of volunteering and working your way up the ladder. Today, it is a highly competitive market. Yet, writes Kumar, “there are still far too many Americans and Europeans leading international aid agencies at a time when there are so many talented Africans, Asians, and Latin Americans who can be making change in their own countries.

“Changing these kinds of nationality requirements will require a groundswell that is hopefully coming soon. In fact, until 2018, the International Organization for Migration, a UN agency, had for fifty years always had an American at the helm. But after President Trump put forward an American candidate who was accused of making anti-Muslim statements, a Portuguese candidate was elected to the role.”

Kumar’s organization, Devex, has found that young people are more and more interested in making careers in the aid industry, demanding jobs in for-purpose programs. This is especially true for jobs in regions where there is so much need due to prolonged fragility, violence, extremism, ethnic conflict, geopolitical machinations, climate change, and catastrophic, yet preventable or treatable diseases, such as polio, HIV, malaria, guinea worm, diabetes, and so on. Yet, professionals with the right experience are hard to find. Many young people are laden down with student debt and must work toward lessening that before accepting these lower paid jobs in the aid industry. Their desire to work for purpose will have to be put on hold.

What our corporate and political leaders, not to mention the billionaire foundations, can do is “find ways for people who want to make a social contribution to do so – even if that is not currently the core mission of the company.”

Kumar ends his book by asking “Can We Get There?” He discusses a recent interview he had with Bill Gates on the prospects for achieving the First Sustainable Development Goal – ending extreme poverty – by 2030. Gates argued that the end of extreme poverty is itself a kind of arbitrary goal, and even the World Bank’s technical definition of ending extreme poverty allows for 3 percent of a country’s population to remain under the poverty level. The reduction of childhood deaths in many countries has meant more kids living in poverty with a lack of nutrition. So, Gates is not optimistic that 2030 is the year extreme poverty will disappear, but says “we’re making incredible progress.”

When we contribute toward the progress to zero-poverty, Kumar says, we will indeed have an “enduring gift” for ourselves as well as for humanity.

“‘Poverty’ and ‘charity’ are two old ideas that have been integral parts of the human experience for millennia. ‘Progress’ is a relatively new one. It contains within it the sense that what has come before can be changed. That we are not consigned to our present circumstances. That even as we pass milestones and achieve goals, there will remain more to do.”

Creating a Learning Society

A New Approach to Growth, Development, and Social Progress

Joseph E. Stiglitz

A Nobel economist and a leading finance expert posit the view that learning is more important to growth and development than the accumulation of capital. The traditional view of an inherently efficient free market, and of government regulation as the major source of economic difficulty, impedes the raising of a society’s standard of living by discouraging the production and dissemination of knowledge.

In the series: Ending Global Poverty

Related articles:

Further Reading

External Stories and Videos

GSMA Announces Seven New Grant Recipients from the Mobile Money for the Unbanked Programme

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

The GSMA announced the details of a further seven grantees from the Mobile Money for the Unbanked (MMU) Fund, which is administered by the GSMA Foundation, Inc., with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Lebanese are Tired of Hosting Syrian Refugees

Edward Gabriel, The Washington Institute for Near East Policy

Not only is there a deteriorating humanitarian crisis in Lebanon but also many Lebanese blame the strains of their country on the 1.5 million Syrian refugees who remain in the country. Without the partnership of the United States, Lebanon, and the international community, we fear these suffering refugees and host communities will become even bigger losers in a larger regional conflict.

The Ford Foundation Just Made a Billion Dollar Bet on Impact Investing

Ben Paynter, Fast Company

Like many major philanthropic funders, the Ford Foundation for social justice spends roughly 5% of its annual endowment on charitable causes, reinvesting the rest to ensure it will be able to recoup those costs and operate in perpetuity.

Mobile Money Services Like M-Pesa Key to Poverty Reduction in Africa

Kevin Mwanza, The Moguldom Nation

M-Pesa, the world’s largest mobile money network, could be the key to poverty eradication in the developing world based on its success in Kenya where almost 200,000 households headed by women are living above the poverty line as a result of the innovation, according to a study by Journal Science.

Operating Model for GiveDirectly

GiveDirectly

The GiveDirectly nonprofit that lets donors send money directly to the world’s poorest.

China’s New Aid Agency: What We Know

Devex

Wang Xiaotao is the first director of the China International Development Cooperation Agency. Just who is Wang Xiaotao?

Neighbor Nations Can’t Bear Costs of Venezuelan Refugee Crisis Alone

Dany Bahar & Sebastian Strauss, The Brookings Institution

The ongoing massive exodus of Venezuelans into neighboring Colombia and other South American countries has the potential to become the largest refugee crisis since the eruption of the Syrian civil war.

Charity Navigator

Charity Navigator is a website that provides “objective ratings” to help donors find charities they “can trust and support” instead of giving money to organizations that might waste it.

Other agencies, such as GuideStar and San Francisco’s GiveWell program, are more subjective and offer standard metric analyses in determining which programs are the most effective for immediate and shorter-term needs. However, these types of guides focus mainly on “narrow impact metrics” which may not address the cycle of poverty itself.